Mary Elizabeth, a redheaded woman in exercise clothes, is holding an extremely bald, blubbery baby when she answers her door. She’s smiling through the exhaustion of new parenthood and is almost gushingly friendly. She wants to let the Environmental Voter Project intern on her doorstep know that she really appreciates what her visitor is doing, really. And yes, of course she’s going to vote in the upcoming election, it’s so important! But she can’t really talk right now.

I’m standing on the porch with said intern — Adrienne La Forte, a junior at Tufts University who looks like a cross between Zooey Deschanel and Frances Bean Cobain, but in Tevas — to get that exact promise. So we don’t really need more of Mary Elizabeth’s time. We’re done here.

Chasing more people for the same pledge, we continue down this street in the Boston neighborhood of Jamaica Plain and ascend the steps belonging to Carlos the piano player. He’s not home. We ring the doorbell belonging to Alex the ballerina. She’s not there either.

Each of these people is an environmentalist — at least, according to the algorithm that generated the canvassing lists we’re using to guide us to each door to knock on. That algorithm analyzes a combination of consumer and demographic data to identify Mary Elizabeth and Carlos and Alex as people who probably consider the climate and environment among their top political priorities and may need to be encouraged to vote. According to the Environmental Voter Project, it is roughly 89 percent accurate. We know with 100 percent accuracy — because it’s public information — that Mary Elizabeth and Carlos and Alex have missed the last few elections. La Forte is coming by to urge them to turn up for the September 4 primary here in Massachusetts.

When she wasn’t working at Anthropologie to pay rent, La Forte went door to door all summer long to ask each of these people ID’d by the algorithm whether they plan to vote in the upcoming primary. If they do, would they mind signing a pledge to promise to follow through? She’ll mail it to their house later, ahead of the election, just as a nice reminder.

It all sounds pleasant enough, but it’s actually psychological manipulation. The idea behind her request is to tap into these voters’ desire to project the best versions of themselves — that is to say, people who are committed, engaged, and follow through on a promise.

The EVP sees itself as a field lab, testing and honing the best ways to get environmentalists to appear at the polls. That’s it. They offer no arguments about why environmental issues matter, no attempts to convince their targets why voting is important, no pressure to vote for any particular candidate. Just: Will you vote? Promise?OK. The reason why is that environmentalists are very bad at voting. In the 2014 midterm election, for example, 44 percent of registered voters showed up. Just 21 percent of registered voters who consider themselves environmentalists did.

The EVP headquarters is merely a modest shared office in downtown Boston, peopled on any given day by three full-time staffers and roughly half a dozen interns. It also counts on a coordinated team of volunteers scattered across the nation, from the Boston HQ to Boulder.

But its goal is outsized: It plans to save the planet by getting environmentalists to be their ideal selves. Which is to say, environmentalists who vote.

The canvassing is just part of it. Getting people to the polls, for the EVP, is an integrated operation including phone calls, text message campaigns, direct mail, email, and online ads. The wording and formatting of each of these are meticulously tested — that’s the “lab” part of the operation.

You will find nary a mention of “environment” in anything the EVP does, except for the organization’s name. That is by design. “All the messaging we test is simply focused on one thing: What will increase the likelihood of voting?” EVP founder Nathaniel Stinnett says. “Talking about intricacies of candidates or races or issues doesn’t get the best results, so we don’t.”

For instance, in Tuesday’s Massachusetts primary, traditional political observers are watching upstart congressional contenders like Gamergate heroine Brianna Wu, and Ayanna Pressley — the first woman of color elected to Boston’s City Council. Pressley is now challenging a long-stagnant seat in the House and just netted a coveted endorsement from the Boston Globe. But at EVP, you’ll never hear those names or those of their opponents. Instead, project employees talk about the fact that the election date was moved from September 18 — the eve of Yom Kippur, theJewish holiday if you’ve got some sins to atone for — to the Tuesday after Labor Day weekend.

Between the timing and it not being a presidential election year, the primary is likely to be pretty dead. But for Stinnett, it’s a golden opportunity to get long-absent voters to the polls and attract some notice from those in office. “We love elections like this!” he says, with glee that approaches mania.

If you don’t vote, goes Stinnett’s rationale, politicians don’t care about what you think. So if you’re the most fervent environmentalist in the world but you never appear at the polling station, no one in Congress will pay two seconds of attention to you or your concerns about climate change or conservation or clean energy.

But if you do vote — especially in the sleepiest, least sexy elections imaginable, like this midterm primary in Massachusetts — Stinnett is certain politicians will start to pay attention to what you care about. And they’ll push for laws and policies that reflect your beliefs.

In a nutshell, that is the goal of EVP and its tests and messaging campaigns and esoteric techniques. “Climate change is not a small issue — it’s an existential crisis,” Stinnett says. “And not using cutting-edge scientific tools to try to solve this problem is inexcusable.”

The tactic of getting people to the polls by playing on their psychological habits, biases, and quirks is now roughly 15 years old. In 2004, then-Harvard Business School graduate student Todd Rogers became an acolyte of Richard Thaler, a pioneer of behavioral economics and subsequent Nobel laureate. Rogers was one of the first to meaningfully apply behavioral psychology to practical politics, says Sasha Issenberg, author of The Victory Lab, the definitive book on data-driven political campaigns.

In 2006, Thaler informally invited Rogers into a group of now-legendary social scientists, which included, among others, Richard Cialdini, a famous scholar of the psychology of persuasion. The group’s members realized that the enormous body of research on human decision-making had never been applied to voter psychology, Issenberg says, so they set out to correct that oversight.

The following year, Rogers founded the Analyst Institute, a data-driven, behavioral psych-oriented political consultancy. It targeted voters on behalf of the AFL-CIO, and later consulted for other politically progressive organizations, including the 2012 Barack Obama presidential campaign (more on that shortly.) Meanwhile, Rogers — now a professor of public policy at Harvard — continued to publish research on voter psychology with other academics.

A 2009 Rogers study found that “high turnout” messaging (i.e., telling voters “Everyone is voting tomorrow!”) yielded better results than low-turnout alternatives (i.e., telling them “No one is voting tomorrow — so you must!”). In 2010, his research suggested that asking how a prospective voter will go about voting (such as, “Do you have a voting plan?”) was more effective than simply asking “Are you going to vote?” In 2016, he found evidence that the promise of a follow-up (“Did you vote yesterday?”) would increase the likelihood that a person would actually head to the polls — and be able to answer in the affirmative.

There are predictable and consistent reasons that people vote, Rogers and other social scientists found: We don’t want to disappoint our peers, family, and friends. We want to live up to some ideal of ourselves, to be the type of person our teachers and parents coached us to be — one who participates in society and civic life.

The reasons we don’t vote: We forget. We had to work a double shift. We don’t have anyone to watch our kids for half an hour and don’t want to deal with dragging them to an un-air-conditioned elementary school. We don’t actually know who any of the candidates are — and feel bad about not knowing. Or our state government may have methodically set up barriers like ID laws and voter purges to keep us from the polls.

The essential point is that few of these obstacles have to do with a deliberate refusal to vote. They’re mostly behavioral — which means they can be shifted simply by changing how people act, rather than how they think.

In 2012, the Obama campaign contracted the Analyst Institute to help turn out voters for the then-president’s reelection effort. The Institute’s staffers shaped the messaging, but more importantly, they introduced a methodology to test its effectiveness. The approach was twofold: First, they randomly tested their communications on a massive group of subjects, sending out different types of persuasive mailings and then following up with surveys to assess each one’s impact. Second, they figured out how to use demographic and consumer data to identify a set of persuadable potential voters.

On November 6, 2012, when Barack Obama was reelected as president of the United States, his campaign attributed the narrow margin of victory in part to that data-enabled targeting.

Directing this attention toward people who typically don’t vote, however, is a relatively new development. New York State congressional candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has, again and again, attributed her recent surprise success in the Democratic primary to the fact that she pays attention to the non-voters who so many candidates ignore. As cofounder of Data For Progress Sean McElwee recently pointed out, non-voters who are also people of color are more likely to support progressive policies in general, including legislation necessary for environmental benefit, such as regulating carbon emissions.

As Stinnett repeats over and over again, the organization does not target groups. It is more specific than that. It is targeting Mary Elizabeth, Carlos, and Alyssa in Jamaica Plain. And if Mary Elizabeth, Carlos, and Alyssa show up to the polls, that’s all that matters.

“[We’re] greatly appreciative of EVP’s work,” says RL Miller, political director of Climate Hawks Vote, an organization that works to elect pro-climate action candidates. “To paraphrase Ocasio-Cortez, stop chasing voters who swing from left to right, and instead focus on swinging non-voters into becoming voters.”

In those words, it sounds straightforward. But actually putting the idea into practice has been years in the works.

Nathaniel Stinnett is an energetic man — so energetic, it’s almost intimidating. With deep-set steel-blue eyes and nary a hair on his head, he looks like Lex Luthor attempting to pass as a Somerville accountant, complete with Red Sox ball cap, gingham shirt, and chinos.

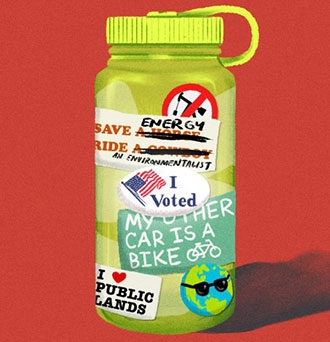

He laser-focuses his intensity on a conference table surrounded by interns, peering at each one by one, as he offers a seminar on the psychology behind EVP’s strategy. Most of the interns come from Boston-area colleges. Their laptops and Nalgenes are festooned with exactly the stickers you might expect from a roomful of environmental nonprofit interns: “I <3 Public Lands,” “Winner Winner Tofu Dinner.” They are rapt and nodding.

After more than a decade volunteering for political campaigns and working as a land-use attorney, Stinnett (a 2016 Grist 50 honoree) founded EVP in 2015. He was amazed by the new scientific rigor being deployed by campaigns and organizers, who were harnessing lessons from behavioral science and running tests to target voters with high levels of confidence. “It made me realize the power of being able to identify someone who you’re pretty confident agrees with you, because that opens up a world of possibilities,” he says. “You can focus on just changing their behavior.”

The strategies EVP uses today are outgrowths of the ideas and studies developed by Todd Rogers and his peers. Since EVP’s beginnings in Massachusetts, its operations have expanded to six states in total, including Pennsylvania, Nevada, Colorado, Georgia, and Florida. Stinnett is looking at adding a handful of states in 2019, including Arizona, Texas, and Virginia. Although still small, the project has garnered the attention of some big guns: Jeremy Grantham, the billionaire British financier who’s recently devoted his considerable fortune to fighting climate change, is now one of its primary funders.

In each state, EVP deploys the same set of tools. First, it generates voter lists, using the hundreds or thousands of data points about you and other potential voters that are widely available: publications you read, the products you buy, the organizations or companies that have paid you, the organizations or companies that you have paid, your sports-watching habits (really!), your religious affiliation, your age, your ethnicity, etc.

To be clear, this is not a Cambridge Analytica situation, which involved misleading tactics and the illicit use of personal data. It’s all legal, and all based on the clicks you make and the cookies you accept.

All smushed together, that data creates a picture of who you are. If you’re yelling “I CAN’T BE DEFINED BY THOSE THINGS!”: It’s too late. You can be. This voter dossier-style process came into fashion early on in Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. That means campaign strategists have used each of your most mundane selections to profile you — and subsequently predict the preferences of others who like the same things you do — for more than a decade.

The payoff is the ability to pinpoint green voters, because people who hold certain combinations of preferences tend to also prioritize environmental issues. Take one example from an actual micro-demographic: If you are a Catholic, African-American male forestry worker who enjoys watching basketball, you’re more likely than the average person to pick climate change as your pet political issue. That’s even more likely if you also have an aol.com email address.

EVP contracts with Clarity Campaign Labs, a data company that assigns you a score based on a statistical model measuring how likely people like you are to prioritize the environment. EVP then checks those scores against voting records to identify targets: People predicted to care about environmental issues who have missed more than a few recent elections.

Armed with algorithmically generated lists, each intern spends a few hours each day toting a stack of about 100 voter pledge cards around to doorsteps. She — they’re almost entirely young women — will ask the target whether they plan to vote in the upcoming election. If they say yes, she’ll ask them to sign a pledge card indicating as much, which will then be mailed back to him in advance of the election.

“This reminds them in their own handwriting of what they are and what they want to be,” Stinnett says.

Then there’s the follow up: Phone calls and text messages remind the recipient that everyoneis going to vote, since that sort of peer pressure is proven to be effective. Facebook ads with Insta-spirational, REI-styled stock photos of attractive people in the outdoors declaring “Good environmentalists vote” also tap into the tendency of people to be influenced by images of what they want to be. Strong, consistent voting habits, like shiny cheekbones or a butt that looks good in athletic leggings, are portrayed as something you want to have.

EVP’s strategy is a long game: Get more environmentalists to vote regularly, put environmental issues on political radars, hope that legislation shifts in that direction.

Recent elections suggest the first step of the EVP approach is working. In this May’s Georgia primary, EVP’s target group of environmentalists-who-don’t-vote had a turnout that was 1.4 percentage points higher than a randomly selected control group of similar people who EVP didn’t approach. In Nevada’s June primary, the voters EVP went after were 1.1 percentage points more likely to vote than the control group. In Colorado’s primary that same month, EVP’s targets showed up 0.8 percentage points more than the control. These sound like small effects, but each is equivalent to the slim sorts of margins — a few thousand or even hundred votes — that can decide a very tight race.

After all, environmentalist non-voters are low-hanging fruit that nobody else is picking right now, says Steve Valk, director of communications with the Citizens Climate Lobby, an organization that works with congresspeople to support pro-climate legislation. “If you can get a significant number of those non-voting enviros to go to the polls — well, you’ve got a lot of competitive races out there, and it could make a difference,” he explains. “If you see some surprises on the November election night, if something happens where the Senate flips, I wouldn’t be surprised if the EVP’s work had something to do with it.”

The prongs of the EVP’s strategy — data analytics and behavioral psych-based methods — each undeniably contains a potentially icky element, because, well, you’re assessing people based on their personal data and trying to use it to manipulate their behavior. But according to Sasha Issenberg, if promoting civic-minded behavior like voting requires playing on those biases, so be it.

“If we want to make better decisions or do things in our society’s self-interest, we need to be tricked into doing them,” he says.

EVP’s interns, perhaps unsurprisingly, concur. “I know I sign my data over all the time — my generation doesn’t care as much,” Adrienne La Forte, the sunny intern I’ve been canvassing with, tells me. “If I’m going to be bombarded with ads, they might as well be ads for things that I’m actually interested in.”

Although each project intern is a unique individual, a statistical model based on their habits and demographics could pretty accurately predict the next round of idealistic young people that will fill these jobs. They like nature, they’re inclined to be vegetarian, they’re politically left-leaning, and most are majoring in some environment-adjacent field of study. What these characteristics really signal is that each of these students intends to change the political climate and ultimately, just possibly, save the world. Like the voters they target, they have made pledges to themselves.

Claire Grossi, who wears giant Frida Kahlo earrings, plans to go to school for environmental law. Hannah Muhlfelder, who fell in love with environmental issues when she worked on dismantling a dam in her Massachusetts hometown, wants to be an environmental journalist. Peter Henry, who scribbles everything down in one of those “decomposition” notebooks, wants to be a writer.

It’s easy to dismiss those signifiers as demographic cliches, but in this case, they are more than mere consumer choices. These interns have already committed to becoming the best possible versions of themselves. And maybe in the end that’s the most powerful of all EVP’s secret weapons: living, breathing, door-knocking proof that some people really do follow through on their best intentions.