This year, hundreds of climate scientists sounded the alarm on global warming. And said the time to take action is “now or never.” You might feel like you've heard this warning before. But recently, the alarm bells have actually gotten worse. Case in point: About half of the world’s population already faces water shortages at some point during the year. 1 in 3 people worldwide are exposed to deadly heat stress. But things could go from worse to even worse if nothing’s done to help the planet chill out.

What’s to blame? Scientists are largely pointing the finger at human activity. And are calling on governments to do more. Around the world, countries have teamed up to address climate change with things like the Paris climate deal. They’ve made individual pledges, too. See: China, the US, and India (the world’s top three carbon emitters). But in America, making climate dreams come true may be hanging in the balance.

Enter: The 2022 midterm elections. Aka the fight over Congress and statewide positions like governor, which can call the shots on climate policy with a ‘yea,’ ‘nay,’ or the stroke of a pen. Meaning, 2022 could be a “make-or-break” year for President Biden’s climate agenda. And how you vote could impact what happens over the next few years and even decades.

If you’re wondering how we got to this point, don’t worry. In this edition of Breaking Down the Buzz, we’ll dive into…

-

Why is action on US climate change policy moving at a glacial pace?

-

What do the midterms have to do with climate change? And how can these elections open a new phase of climate action?

PS...Check out our other editions of Breaking Down the Buzz, where we cover critical race theory, marijuana legalization, and misinformation.

A Temperature Check on US Policy

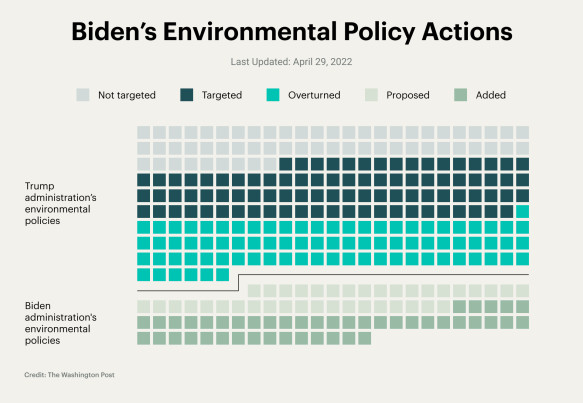

Since entering office, Biden’s been hitting the ‘undo’ button a lot. By one count, he's overturned 78 of former President Trump's not-so-friendly environmental policies. He's also added 45 measures of his own. And brought the US back into the Paris climate deal. This as reports warn that sea levels along the US coasts could rise by an additional foot by 2050 — meaning more flooding. And droughts and heat waves are expected to be more intense in the West.

But the Biden admin’s path toward a greener future has hit some red lights. Earlier this year, the US’s largest effort to combat climate change crumbled. See: the Build Back Better plan. The climate portion (read: $555 billion) would have allowed tax credits for electric vehicles and renewable energy sources (think: solar and wind). None of this would have reversed the effects of climate change. But it would have put the US closer to meeting its goals.

In the end, zero Republicans supported the massive social spending and climate bill. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) effectively killed it in the tied Senate, in part because of the price tag. But critics point to Manchin’s and his state’s coal interests as the real reason he axed the bill. Build Back Better’s lack of a fairy-tale ending isn’t out of the ordinary. Let’s get into…

Why Is It So Hard to Pass Climate Change Legislation in the US?

Congress doesn’t have the best track record for passing climate legislation. One analysis ranked the US 28th in the world for its efforts, behind China and India. And in the last three decades, several policies hit roadblocks (see: this and this). Experts point to a variety of reasons for why lawmakers aren’t sweating over Mother Nature, including…

Competing Interests

The world’s got 99 problems. And climate change is only one. “There are at least two very pressing issues right now,” Kai Schulze, a professor at the Technical University of Darmstadt’s Institute of Political Science in Germany, explained. “COVID — we don't know how that will continue over the year until the midterms. [And] the other thing is the Russia-Ukraine crisis.”

Think about it like this: Gas prices spiked across the country when the war broke out. (Remember: Russia is one of the world's largest suppliers of oil.) And there’s been a rise in coronavirus cases thanks to variants and subvariants. Meaning, conversations about the environment have largely been left on read. It’s not the first time the gov has placed climate change on the back burner. And that brings us to…

Political Divisions

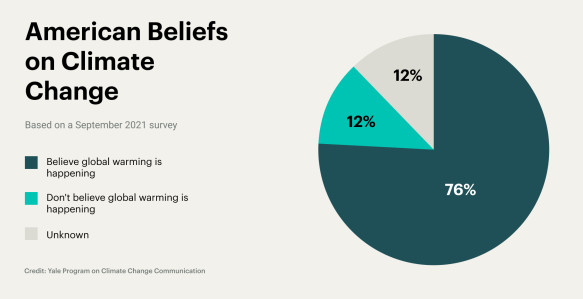

“It is very clear [climate change] has become very politically polarized,” Anthony Leiserowitz, founder and director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, said.

Previous studies have found a link between conservative media bias and a rise in climate denial. “This is a symbiotic relationship between the party members, their leaders, and the media organizations they get their news and information from,” Leiserowitz added. “You are more susceptible to the forces out there who are trying to mislead, misinform, and even disinform the public because they don't want to change the status quo.”

Fossil Fuel And State Interests

A tale as old as time. One analysis found that the top five publicly-owned oil and gas companies spend an estimated $200 million a year lobbying to sabotage climate policies. That’s because swapping to more renewable energy could hurt their bottom line.

Meanwhile, Republican lawmakers think that leaving oil, gas, and coal in the rearview mirror could mean job losses and a wounded economy. Which can impact states they represent. “We have a lot of states…that produce a lot of oil and gas,” Barry Rabe, professor at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R Ford School of Public Policy, explained. “There's a lot of economics. There's a lot of jobs in those states. How do you transition away from that?”

Environmental Political Power

It’s not very strong right now. Even though the majority of Americans worry about the environment. And the climate movement has grown in visibility. It even has a face (hi, Greta Thunberg). But in the US, those interests aren’t coming across on the Hill or at the polls.

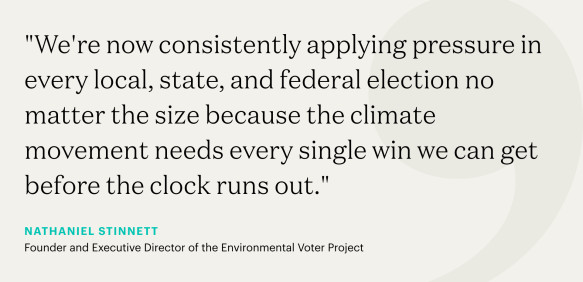

“[It’s] wishful thinking to assume that politicians are ever going to combat climate change, unless voters start forcing them,” Nathaniel Stinnett, founder and exec director of the Environmental Voter Project (EVP), said.

It’s a sentiment Leiserowitz echoed, “You also need people demanding action.”

Predictions For Future Climate Change Policy…The Crystal Ball Says…

Environmental change is TBD, especially when politics is involved. Historically, the president's party loses seats as a result of the midterm elections. It happened to former Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump. And if the GOP wins big in the midterms, climate policy could go on pause for a while.

At the same time, Congress has found some middle ground (emphasis on ‘some’) when it comes to certain legislation. And some experts say there’s still time for lawmakers to get their sh*t together.

“What happens between now and November in Congress could be significant,” Rabe said. “Can Congress put something together or not?...I think we got a sense of where the parties might converge late last year when the infrastructure legislation passed, which had some climate-friendly provisions in it.”

Here are some of the other efforts that’ve been floated out on the Hill:

-

A potential new bill. Democrats are looking to revive the climate portion of the Build Back Better bill. And Sen. Manchin (D-WV) has indicated he might be willing to play ball. But it’s unclear what this new potential legislation could look like.

-

Riding solo. Progressive lawmakers have called on Biden to use his executive powers to take action on climate change. Including by declaring a “national climate emergency.” Climate advocates say this would allow him to use existing resources to combat climate change. Including using more of the Defense Production Act (DPA) to have companies manufacture clean energy.

Other than planned legislation, there are times when extreme weather disasters feel a lot closer to home. One example: California's devastating wildfires and historic drought conditions are leading to larger efforts to tackle climate change in the state. And such climate events may also force Congress to take quicker action.

“Another thing that we know can always have an impact on elections now is if you have extreme weather events or catastrophes,” Schulze said. But many environmentalists aren’t willing to wait for disaster to strike. And are instead taking matters into their own hands.

Climate Change Meets Your 2022 Midterm Ballot

Real talk: Americans think the Biden admin isn’t doing enough on climate reform and are getting frustrated. And some Dems are connecting the dots, saying this could mean low voter turnout come November. But Stinnett says the vibe’s gotta change.

“Our answer, even when we're frustrated by politicians, must be to get stronger and exercise more voting power on election day, not less, ” he said.

Calling All Environmentalist Voters

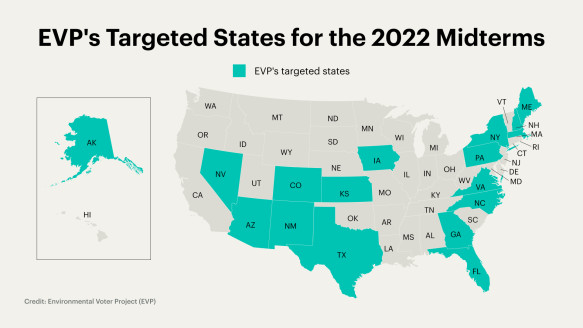

Since 2015, the Environmental Voter Project (EVP) — a nonprofit — has targeted people whose No. 1 concern is the environment. But who haven't shown up consistently at the polls. Ahead of the 2022 midterms, the org’s targeting more than 6 million environmentalists across 17 states who’ve never voted in a midterm election before. EVP’s goal: boost their political power to show politicians what they’re made of.

“If the climate movement wants to start getting climate leadership, we need to get so much political power that these politicians will trip over themselves to do what we want, because it will be how they win elections,” Stinnett added.

And he says that goes for every level of government. At the state and city levels, California’s Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) signed an executive order to phase out new gas-powered cars. And New York City’s working to become carbon neutral by 2050. Meaning, people may feel a greater impact on their lives from climate decisions made at the local level. And for some states, there could be some major change in store this year…

-

‘Hello’ or ‘bye’ gov’na. There are 36 governors' races on the ballot this year. And at least six of them may be tossups. Governors submit state budget proposals — potentially influencing how any climate-designated funds are spent. And they make appointments to their cabinet and state boards and commissions. (Plus, don’t forget about city and town positions, like city council roles, which can also pass policies to reduce emissions and improve energy efficiency.)

Experts say there’s a lot of potential cash flow to states if Congress passes a climate bill. Note: When the infrastructure bill passed, states were expected to get anywhere from $2 billion to $45 billion.

“If some version of Build Back Better for climate passes, it's not like [President] Biden's just going to be sitting [and] pulling strings,” Rabe said. “A lot of the decisions will be made by state governments.”

theSkimm

Climate change is an issue that impacts all of us. This November could set the tone for the next two years of climate change policy. And whether the US takes a leading role in combating an issue that it’s helped create. Don’t sit this one out, vote.

Skimm'd by Maria del Carmen Corpus, Maria McCallen, Alicia Valenski, Kamini Ramdeen-Chowdhury, Clem Robineau, and Niven McCall-Mazza